Editorial Manager, Economic Justice and Narrative Strategy

On Apr. 23, 2025, President Donald Trump signed an executive order targeting a longstanding civil rights enforcement tool known as disparate impact. This legal framework has long served to identify and address discrimination that hides in plain sight, embedded in the structures of hiring, housing, education, and public policy. Though it plays an important role in our society, many Americans may not have heard of disparate impact. Below, we’ll take a closer look at what it is and examine why the president wants to end it.

Unlike the clear and explicit harm inherent in things like “Whites Only” signs, disparate impact focuses on the more subtle ways discrimination rears its head. Specifically, determining disparate impact requires asking a set of important questions: are seemingly fair rules or standards disproportionately harming certain groups of people? And, if so, are those standards truly necessary? If the policy or practice is indeed harming a certain group unnecessarily, then solutions are sought to remedy it.

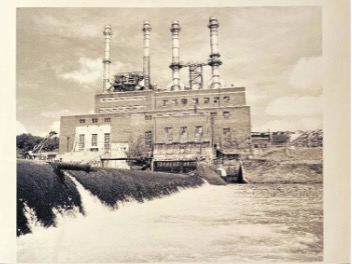

The roots of disparate impact date back to a landmark Supreme Court decision in Griggs v. Duke Power Company. Duke Power, a power-generating facility in Draper, North Carolina, had a history of overtly discriminatory hiring and promotion policies. At the company’s steam station, the best jobs were reserved for white people. Meanwhile, Black workers were relegated to the labor department, where the highest-paid worker earned less than the lowest-paid employee in the other four departments where only white people worked. After the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed such directly discriminatory practices, the company introduced new requirements for certain jobs, including having a high school diploma and a passing score on standardized aptitude tests.

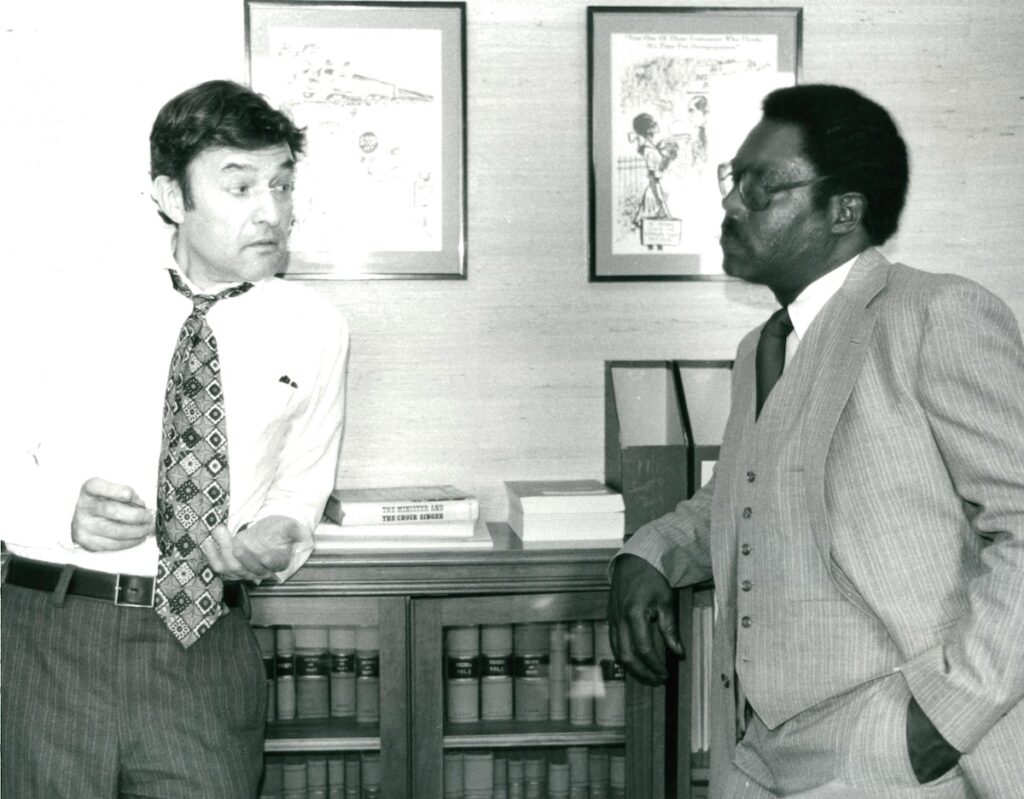

In Dec. 1970, Jack Greenberg, who succeeded Thurgood Marshall as President and Director-Counsel of LDF, presented argument in the Supreme Court on behalf of 13 Black Duke Power employees. Another critical member of the litigation team was Julius Chambers who later became LDF’s third Director-Counsel.

While these new requirements didn’t explicitly mention race, they had a clear impact: Black workers – who had been denied equal access to education under Jim Crow laws – were excluded because of these new requirements and kept out of better paying jobs in the company.

In March 1971, the Supreme Court unanimously sided with the employees, ruling that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act protects employees from being harmed by employment practices that have a clear discriminatory effect — even if the employees could not prove discriminatory intent — unless the practices can be justified by business necessity. Importantly, Duke Power couldn’t show that their requirements were necessary for the jobs in question.

LDF’s success in the case helped change how courts and government agencies understood discrimination, laying the foundation for a broader concept of civil rights enforcement that could address persistent disparities in opportunity, wealth, and resources, not just individual bad actors. Courts and federal agencies would later expand this critical protection to discrimination in housing, schools, hospitals, and other entities funded by the federal government, as well as banking and lending. It likewise extended to discrimination based on other characteristics, including sex and sexual orientation, disability, and age. Later, in 1991, Congress updated Title VII to explicitly include the concept of disparate impact into law.

President Trump’s executive order does not eliminate disparate impact from federal law — he cannot do that unilaterally. The doctrine remains embedded in Title VII and other statutes, and courts are still obligated to consider disparate impact claims. However, by instructing federal agencies to deprioritize disparate impact enforcement, repeal guidance and regulations, and change the government’s position in cases involving these claims, the administration is retreating from one of the most effective tools for uncovering and correcting deeply embedded bias and discrimination. This could have far-reaching consequences for everyone.

Disparate impact has been used to challenge practices ranging from biased school discipline policies to lending criteria that disproportionately deny mortgages to people of color. Without it, individuals harmed by unfair and unnecessary barriers may have fewer tools to seek justice when discrimination isn’t overt and there’s no “smoking gun” evidence to prove discriminatory intent. This shift away from disparate impact could make it easier for employers, schools, and landlords to hide discrimination behind neutral language, even if their policies reinforce deep-seated disparities.

While it may seem like an issue confined to legal debate, disparate impact goes to the heart of how we define fairness. Are we willing to confront not just overt bigotry and racism, but also the more subtle ways that inequality continues? At a time when the United States is reckoning with discrimination in new and urgent ways, understanding and defending the principle of disparate impact is more important than ever.

LDF’s Equal Protection Initiative (EPI) works to protect and advance efforts to remove barriers to opportunity for Black people in the economy, our educational systems, and other areas.

In 1971, the Supreme Court’s Griggs v. Duke Power Co., held that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act protects employees from employment practices that have a clear discriminatory effect.

Project 2025’s proposals, from ending data collection on race to weakening the government’s ability to fight discrimination, will frustrate efforts to remedy racial inequality.