The Legal Defense Fund (LDF) is deeply saddened to learn of the passing of Cecilia “Cissy” Suyat Marshall on November 22, 2022. Ms. Marshall was the wife of LDF’s founder and the nation’s first Black Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, a former staff member and long-standing LDF board member, and a tireless devotee to the cause of equal justice. She passed away in Falls Church, Virginia, at the age of 94.

As a young employee of the arm of the NAACP that became LDF, Ms. Marshall contributed to the exhaustive preparation for the Brown v. Board of Education trial, which overturned the “separate but equal” doctrine of legally sanctioned discrimination and forever changed the American landscape.

After marrying Mr. Marshall in 1955 at St. Philip’s Episcopal Church in Harlem, New York, she faithfully supported him through some of the most trying passages of his career, including his contentious Supreme Court confirmation hearing. After his death in 1993, she acted as a fastidious steward of Justice Marshall’s legacy, giving frequent interviews about their life together and serving with organizations that had been important to him, including LDF.

“It is with a heavy heart that we received the news today of Ms. Marshall’s passing. Ms. Marshall was a civil rights activist, historian, mother, grandmother, widow of LDF’s founder Thurgood Marshall, and a phenomenal supporter of LDF – including as a devoted member of our Board of Directors,” said LDF President and Director-Counsel Janai Nelson. “She also had a robust sense of humor, was kind-hearted, and exuded a mighty force belied by her petite stature. She was a cherished member of the LDF family, and we extend our deepest condolences to her immediate and extended family who shared her with us so generously over the years.”

“It saddens me deeply to learn of the passing of Ms. Marshall, who was a faithful member of the LDF Board, and a great lady. It was my absolute honor to have the opportunity to get to know her, and to bring her closer to the fold of the LDF family during my time as Director-Counsel,” said Sherrilyn Ifill, LDF’s seventh President and Director-Counsel. “Her devotion to LDF, the organization her husband founded and where she once worked as a secretary in her early days, remained undiminished, and she took her Board service seriously. She was the recipient of numerous awards from LDF and lent her name and support to our efforts to support young civil rights lawyers, most recently through the launch of LDF’s Marshall-Motley Scholars Program. I extend my deepest condolences to the entire Marshall family and to my former colleagues on the Board and staff at LDF, in this monumental loss of our beloved Board member.”

“I am saddened by the passing of Ms. Marshall — a national treasure, a shining light, an activist who supported LDF lawyers in the heyday of the civil rights movement and one who fully represented the life, legacy and values of her husband, the late Thurgood Marshall,” said Assistant U.S. Attorney General for Civil Rights and former LDF attorney Kristen Clarke.

Known as Cissy, Ms. Marshall was born Cecilia Suyat on July 20, 1928, to Filipino parents on the Hawaiian island of Maui. The island’s diversity – and its distance from the United States, which it would not join as a state until 1959 – insulated Ms. Marshall from the harsh racial discrimination that plagued America. She reflected on this matter in a 2013 oral history she provided for a joint project of the American Folklife Center, the Library of Congress, and the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture.

“I really didn’t have any idea [of racism] at all, because I went to school with different nationalities, Japanese, Filipino, Chinese,” she recalled. “[I]t wasn’t really until I went to New York that I found out about the racial problem.”

In 1948, Ms. Marshall moved to New York to live with an aunt and uncle. She took stenography classes at Columbia University while searching for a job in the city. A clerk at an employment office sent her to the NAACP, an assignment Ms. Marshall later speculated she was given solely because of her skin color.

“The clerk, she saw my dark skin, and she sent me to the national office of the NAACP,” she told the Washington Post in 2016. “That is the only reason I can think of that she sent me to the NAACP for my first job. And to this day, I thank her, because had it not been for her, I wouldn’t have known anything about a race problem.”

As LDF prepared to argue Brown before the Supreme Court, Ms. Marshall often found herself taking notes on the practice trials in New York and at Howard University in Washington, D.C. “We would work until midnight,” she recalled in the aforementioned interview in the Washington Post.

On May 14, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its decision in Brown, unanimously ruling that legal segregation was inherently unconstitutional. A party quickly erupted in the NAACP offices in New York. But Ms. Marshall recalled that Mr. Marshall did not partake in the celebration for long. “I don’t know about you fools,” the Washington Post reported him as saying, “but I’m going back to work. Because our work has just begun.”

For Mr. Marshall, triumph was quickly followed by tragedy. Just nine months after the Brown decision, his first wife, Vivian Burey, died of cancer. She was only 44. Mr. Marshall entered a period of deep mourning. “[H]e lost so much weight that he became cadaverous in appearance,” wrote former LDF Director-Counsel Jack Greenberg in his history of the organization.

In time, Mr. and Ms. Marshall would grow close and eventually wed. When he first proposed marriage, she refused, concerned that LDF’s leader entering an interracial marriage would create dissension within the organization. “I said, ‘No way. No way. People will think you are marrying a foreigner,’” she recalled in the Washington Post. “He said, ‘I don’t care what people think. I’m marrying you.’ He was so persuasive. So we got married.”

At the NAACP, she served as a secretary to Gloster Current, the NAACP’s then-Director of Branch and Field services. In that capacity, she met NAACP luminaries like Walter White, Roy Wilkins, and Thurgood Marshall. Her job also took her to the South, which brought her face-to-face with the harsh realities of Jim Crow. Barred from most hotels, she and her colleagues often stayed in the homes of local organizers and activists – people whom, according to Ms. Marshall, her husband regarded with deep admiration. In the oral history, Ms. Marshall recalled her husband calling lawyers like himself “cowards” for leaving a city as soon as they had argued their case, in contrast to the locals, who, he said, “put their names on the briefs. They stayed there and met daily opposition, hostile people. They’re the real heroes in this civil rights fight.”

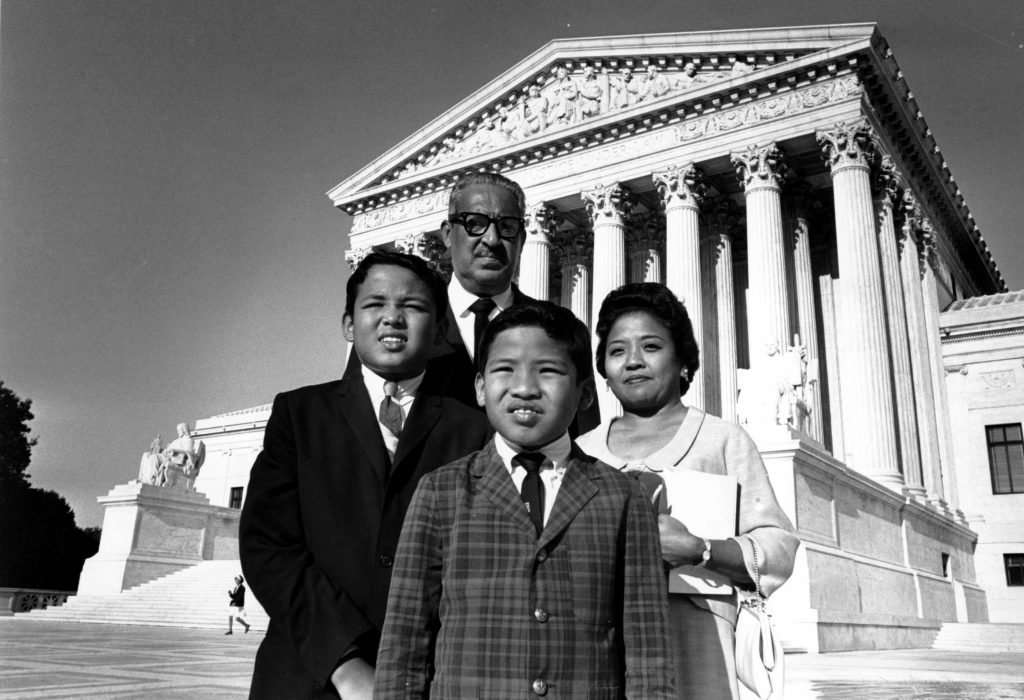

The couple wed on December 17, 1955, at a ceremony in Harlem. The couple’s life together began just as Mr. Marshall’s career was on the cusp of a new level of national influence and visibility. In 1961, President John F. Kennedy appointed Mr. Marshall to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. Four years later, Lyndon Johnson named him Solicitor General, making him the first Black American to serve as the nation’s top litigator. The appointment also made him the highest ranking Black official in the history of the federal government at that time.

But he did not remain at the Justice Department for long. In 1967, President Johnson nominated Mr. Marshall to be an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court. “I believe it is the right thing to do, the right time to do it, the right man and the right place,” President Johnson said in his announcement.

Ms. Marshall learned of the nomination from the president himself. Justice Marshall recounted their conversation in a 1969 oral history:

I said, 'Now, Mr. President, if it’s all right with you I’d like to call my wife.' … He said, 'You mean you haven’t called Cissy yet?' I said, 'No, how could I? I’ve been talking to you!' So we got her on the phone and I told her to sit down. She said, 'Well, I’m standing.' I said, 'well, sit down.' She sat down and he said, 'Cissy—Lyndon Johnson. … I’ve just put your husband on the Supreme Court.' She said, 'I’m sure glad I’m sitting down.'

- Thurgood Marshall

Her husband’s path to the Supreme Court was far from smooth. For five days, Mr. Marshall testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee, which was chaired by the Mississippi segregationist James Eastland. LDF’s Greenberg called the hearings “brutal,” a public spectacle “in which racism once more reared its ugly head.” The process was deeply stressful for Mr. Marshall, who feared that his nomination would be scuttled.

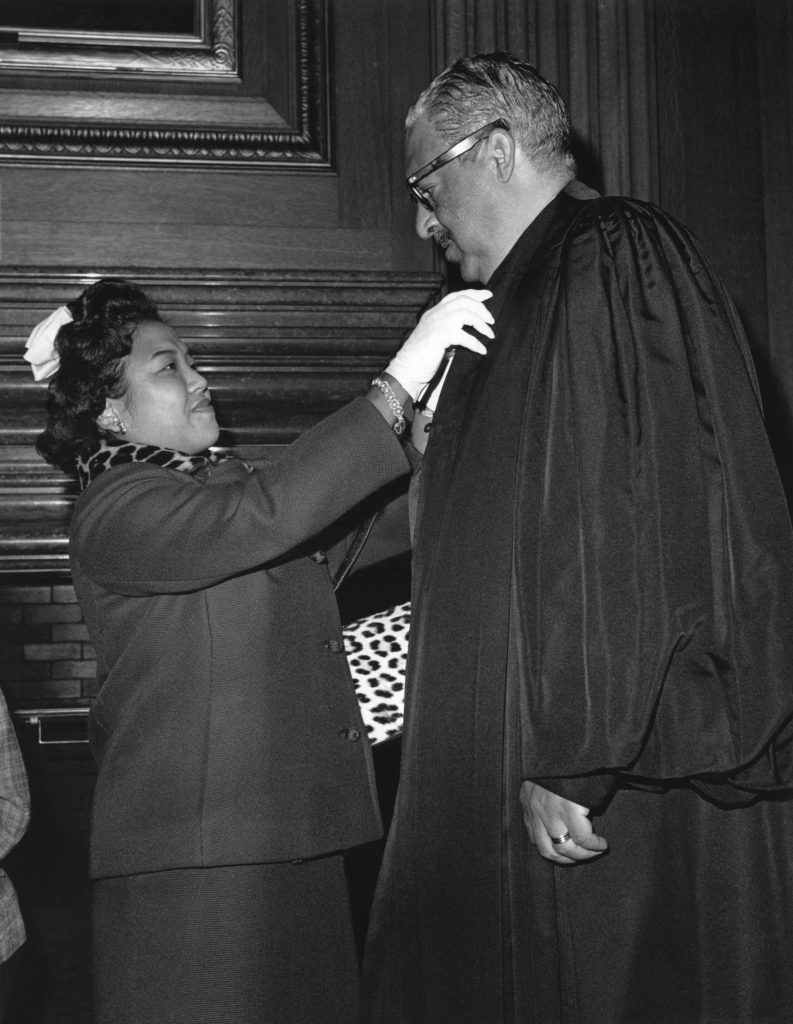

Ms. Marshall was a constant and calming presence throughout the hearings, showing her support for her husband by patiently sitting through each day of testimony. She understood that, as the Filipino wife of the first Black man nominated to the Supreme Court, she was under more scrutiny than most nominees’ spouses. As Will Haygood wrote in Showdown, his history of the Marshall confirmation battle:

“No black man had ever had such a public coming-out in America, where his life’s work had been laid out and examined, as Marshall was now going through. Additionally, it was rare to see a public figure in an interracial marriage. Cissy Marshall – elegantly attired every day of the hearings, wearing her thin white summer gloves – endured the stares alongside her husband with grace.”

Justice Marshall was ultimately confirmed on August 30, 1967, by a vote of 69-11. He was sworn in that October. Ms. Marshall enjoyed pointing out that her husband took the oath from Justice Hugo Black, a former Klan member who became one of the more liberal members of the court, and who had joined the unanimous Brown opinion in 1954.

Her husband served on the Supreme Court until his retirement in 1991. He died in 1993. The couple had two sons – Thurgood Marshall, Jr., a lawyer who served as an advisor to President Bill Clinton, and John Marshall, who served as the first Black director of the U.S. Marshals Service from 1999-2001, and as Virginia’s Secretary of Public Safety from 2002-10.

Ms. Marshall always spoke with deep pride about the indelible mark her husband left on her and her sons. “Seeing his sons grow up to become adults … has been a great joy,” she said in a Seattle Medium interview in 2017. “My husband gave me and all of us a great life and his favorite slogan was something we’ve always lived by and I still live by today, especially when I think of the state of things in this country.”

She added that the slogan was, “Never give up.”

After her husband’s death, Ms. Marshall kept his legacy alive through interviews, speaking engagements, and service on LDF’s Board of Directors, which she joined in 1988. Proud of what her husband and his colleagues achieved; she always emphasized the work that was left to be done.

“We have much more to do until we secure for every disadvantaged child and adult full and complete equality,” she said in a 2004 address to the American Bar Association on the 50th anniversary of Brown.

Ms. Marshall remained an active member of LDF’s Board of Directors for many years and served over the tenure of five of the organization’s eight President and Directors-Counsel. She is fondly remembered for her engagement with the staff over the years and her abiding interest in LDF’s work and leadership. “Ms. Marshall would attend meetings in person and eventually by phone and was always attentive to the goings-on of the organization and its progress,” said Nelson.

“We are deeply saddened by the loss of Ms. Marshall, our Board colleague and friend of many years,” said Angela Vallot and Kim Koopersmith, co-chairs of LDF’s Board of Directors. “An instrumental part of LDF’s legacy, Ms. Marshall was involved in the strategic work of the organization through her long and dedicated participation as a member of the Board of Directors. Her lifelong commitment to racial justice and equity was unwavering and we were delighted to be able to honor her several times for her service. We will miss her dearly.”

“Cissy Marshall was an important part of Thurgood Marshall’s story and in her own right a part of the civil rights story of her time. She represented LDF’s continuing link to its first Director-Counsel,” said Ted Shaw, LDF’s fifth President and Director-Counsel. “Cissy was a stalwart supporter of LDF and each of its directors-counsel, and a long-time Board member. On a personal level, I can recall many wonderful times in which she shared her wisdom, her commitment, and her wit. We were blessed to have known her.”

Ms. Marshall lived by her own words, lending her presence to the ongoing struggle for equality. She drew headlines in 2013 when she attended the oral arguments before the Supreme Court in Shelby County v. Holder, the case that would eventually invalidate the preclearance requirement of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

“I’ll never forget the hush that came over the courtroom when Cecilia Marshall, widow of former Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, and [the late] civil rights hero U.S. Rep. John Lewis … entered the courtroom,” wrote LDF’s then-deputy director of litigation Ryan Haywood in the Houston Chronicle. “The fact that they were there to witness the arguments signaled – for anyone who didn’t already get it – the weight of the issue before the court.”

“What I appreciated most was Ms. Marshall’s warmth, energy, and sense of humor – and her fulsome embrace of LDF’s leaders and staff,” said Ifill. “She was a meticulous caretaker of her husband’s legacy and delighted in seeing the growth of young LDF lawyers who were following in the path he created. Ms. Marshall also revered the Supreme Court and enjoyed her membership in the circle of spouses of former Supreme Court justices. On the rare occasions when she attended oral arguments in the Court, it always seemed to me that everyone sat up a little bit straighter. I know I did.”

In 2014, Ms. Marshall accompanied members of the LDF Board to the White House on the 60th anniversary of the Brown decision where the attendees met with President Obama, who recognized the connection between his own presidency and the work of Thurgood Marshall and LDF.

Looking back on her life at the center of the civil rights struggle, Ms. Marshall often expressed wonder and gratitude for the things she had witnessed firsthand. “I just want to say it’s been a blessing,” she recalled in her 2013 oral history. “I think I live a charmed life.”

Ms. Marshall is survived by her two sons, Thurgood, Jr., and John, and her four grandchildren, Thurgood William, Edward Patrick, Melonie, and Cecilia.

Donations in memory of Ms. Marshall can be made here.

(Read the Washington Post and New York Times coverage of Ms. Marshalls passing.)