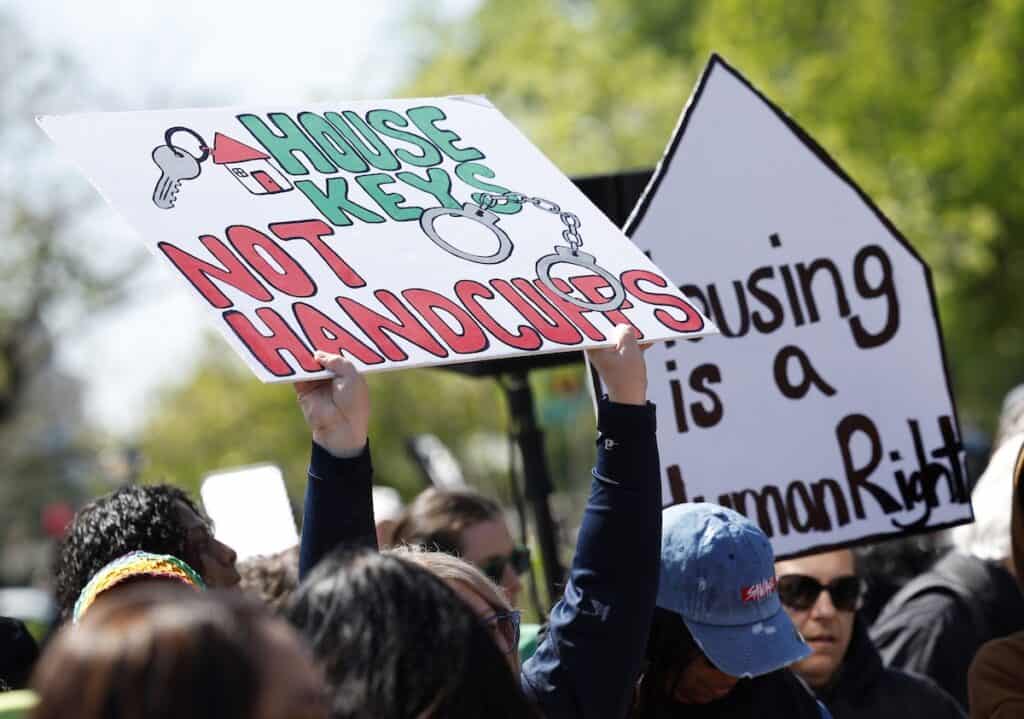

On July 24, President Trump issued an executive order (EO) entitled, “Ending Crime and Disorder on America’s Streets.” This regressive order aims to increase punishment through policing and institutionalization of people who are unhoused and criminalization of programs that offer harm reduction services. It also seeks to pressure state and local governments, nonprofits, and other service providers to use these costly, punitive methods instead of proven strategies to reduce homelessness, such as “housing first” programs.

It urges increasing federal funding to municipalities that enforce laws prohibiting “urban camping,” “loitering,” and “urban squatting” under the guise of “fighting vagrancy."

The roots of vagrancy laws date back to Black Codes, enacted after the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments granted newly freed Black people certain rights. These vagrancy laws were enacted to prohibit Black people’s freedom of movement.

Loitering laws have similarly served to limit the use of public space by people deemed “out of place” by police or other members of the public.

Civil commitment is a legal process that permits the government to detain people against their will who have not committed crimes. These institutions cost taxpayers thousands of dollars without solving the underlying needs for safe, affordable housing or ensuring that people can access care if needed when they leave.

Housing first programs are effective strategies for ending homelessness that prioritize meeting people’s basic need for safe housing. These programs often offer medical and mental health treatment and other services and have been shown to improve outcomes for people who are unhoused and reduce costs to state and local governments.

The executive order cannot change how state and local governments address homelessness on their own. While the Trump administration can threaten to limit federal funding, state and local governments have the power to choose the housing policies that are best for their communities.

The federal government cannot direct local or state law enforcement agencies.

Federal grant programs are created and funded by Congress, and federal agencies may not be able to impose new conditions on grants without congressional approval.

The EO claims, without support, “[n]early two-thirds [or 66%] of homeless individuals report having regularly used hard drugs like methamphetamines, cocaine, or opioids in their lifetimes.” However, according to 2022 HUD data, only 16% of people who are unhoused (unsheltered, in emergency shelter, or transitional housing, or 95,001 of 582,484 people) report chronic substance abuse.

It also claims without support, that “[a]n equally large share of homeless individuals reported suffering from mental health conditions.” Yet, according to 2022 HUD data, only 21% of people who are unhoused (122,888 out of 582,484 people) have severe mental illness.

Moreover, the relationship between substance use, mental illness and lack of housing is complex. According to the National Coalition for Homelessness, many people who are unhoused develop mental health or substance abuse issues after prolonged periods of homelessness due to the lack of safe and affordable housing.

In 2023, a full-time minimum wage worker could not afford an apartment in any state, city, or county in the United States. Currently, the United States has a shortage of 7.1 million rental homes affordable and available to renters with extremely low incomes. Only 35 affordable and available rental homes exist for every 100 extremely low-income renter households.

Housing discrimination remains a persistent problem that prevents people from finding a place to live. From Oct. 1, 2023 through Sept. 30, 2024, the federal government alone received over 8,000 complaints of housing discrimination based on race, disability, sex, religion, and other protected characteristics.

Study after study show that the best way to address homelessness is to provide people with safe, affordable housing and to offer additional supports and services if needed.

At the same time President Trump claims to address homelessness, he has proposed cutting the amount of funding for federal rental assistance programs in half, leaving thousands of individuals and families without the help they need to afford a place to live. The Trump administration has also proposed cutting funding for programs that would help preserve affordable housing and build new affordable housing.

In order to address homelessness, we need to ensure all people can access affordable housing and we must improve access to community-based medical and mental health treatment for those who need it. We also need to address persistent housing discrimination by funding fair housing enforcement and eliminating discriminatory barriers to housing, including criminal history restrictions and source-of-income discrimination.

This Brief focuses on the denial of housing opportunities to people with prior criminal legal contact and the racially discriminatory impact that follows.

This framework is a starting point towards real safety that includes alternatives to policing, community based responders, and public investments that provide economic security and address the root causes of violence.

This toolkit by LDF and the Bazelon Center aides advocates and legislators in advancing strategies to prevent police violence and achieve lasting change for Black people with disabilities.