SENIOR RESEARCHER and Statistician, THURGOOD MARSHALL INSTITUTE

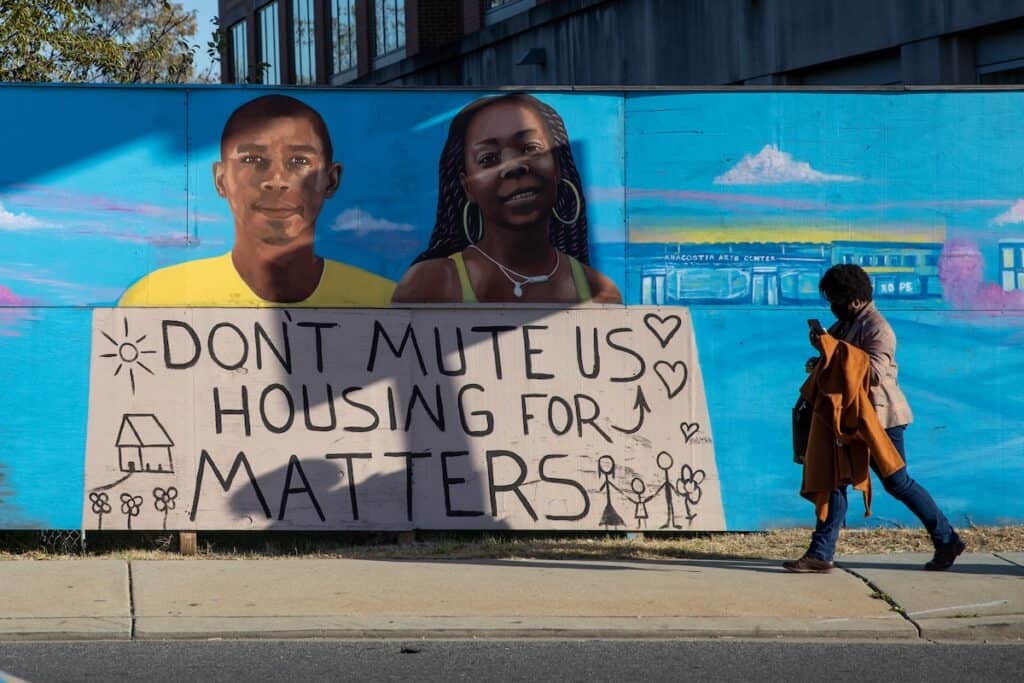

We all know that cities across the United States are experiencing an affordable housing crisis – we see the consequences every day. In an effort to address this crisis, many cities are taking legislative steps to keep families in their homes and prevent racial discrimination against tenants, including through new “good cause” eviction laws. However, state preemption has blocked many of these local efforts, posing threats to democracy and affordable housing access, with especially severe consequences for Black people.

Black families have been hit particularly hard by the affordable housing crisis. In 2022, 57% of Black renters and 30% of Black homeowners were cost-burdened (paying more than 30% of their income on housing) – the highest rates of cost burden of any racial/ethnic group. Additionally, research from around the country demonstrates that Black renters are evicted at higher rates than white renters. I recently conducted an analysis of Maryland and New York which found that communities with more Black renters face significantly higher rates of no-fault eviction filings (i.e. evictions unrelated to paying rent on time or abiding by the terms of the lease). This finding suggests that majority-Black neighborhoods face higher rates of discriminatory or retaliatory evictions.

Good cause eviction laws have the potential to advance fair housing by protecting Black tenants who may face a disproportionate risk of retaliatory or discriminatory evictions. Good cause eviction laws prevent landlords from evicting tenants unless they have a “good cause.” They provide tenants with a baseline right to remain in their homes so long as they are abiding by the requirements of their lease.

Good cause eviction laws can complement other affordable housing policies like rent regulation, source of income non-discrimination, and inclusionary zoning. However, many cities have been foiled by state laws that preempt these changes. Much of the fair housing preemption research has been focused on these latter policies. Less is known about the landscape of good cause eviction preemption and its potential impacts on Black renter households.

Housing is underregulated at the federal level, with tensions between state and local regulatory authorities, making it an area that is ripe for state preemption of local policies. A trend of state preemption of fair housing policies began in the 1980s, with a dramatic rise in the late 2010s. Fair housing preemption most often occurs via state laws that grant specific property rights to housing developers and owners and in doing so restrict the ability of local governments to adopt certain tenant protections.

The Center for Public Health Law Research at Temple University and the National League of Cities have tracked state preemption laws related to rent regulation and inclusionary zoning from August 2019 through December 2024. They found that 34 states have laws preempting rent control and 10 states have laws preempting mandatory inclusionary zoning ordinances. However, state laws that preempt good cause eviction have not been systematically tracked.

New York serves as a forewarning to other states of the potential role of state laws in intentionally or unintentionally preempting local good cause protections. For years, statewide good cause protections had stalled in the New York legislature, so cities like Albany, Poughkeepsie, and Newburgh proactively enacted their own local good cause laws. Landlords challenged these laws and the courts ruled that state law governing evictions implicitly preempted local good cause protections. While the state still has not passed statewide good cause protections, in 2024, it passed a good cause law that gave municipalities the option to opt-in to good cause protections, so that these local policies would no longer be preempted by state law. At least 15 municipalities have opted in.

As local jurisdictions around the country increasingly consider adopting good cause eviction laws, there is the potential for implicit or explicit state preemption, which may exacerbate the racialized consequences of the housing crisis.

The practice of state governments usurping local control has deep roots in white supremacy and the suppression of local Black political power. Since the rise of local Black political power following the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, abusive state preemption and state takeovers have disproportionately targeted many majority-Black jurisdictions.

Research suggests that fair housing laws are more likely to be blocked in states with more racial diversity. In a national, longitudinal study seeking to identify the predictors of whether a state preempts an affordable housing policy, researchers found that one of the strongest predictors of affordable housing preemption was a state becoming more racially and ethnically diverse. The researchers speculate that this finding may reflect a declining white majority using state preemption to block advances in racial justice and maintain systematic advantage in the housing sector. This research raises the alarm that state preemption in affordable housing, like state preemption in other sectors, is being weaponized in a racialized manner.

Research also demonstrates that affordable housing preemption can have public health consequences and worsen racialized health disparities. One study found that adults (of all races) living in states that preempt inclusionary zoning were more likely to report worse overall health status even after controlling for state- and individual-level factors, and Black adults were the only racial group that was more likely to report delaying medical care due to cost. This study demonstrates that state preemption of fair housing policies can result in worse health outcomes for everyone, especially for Black people.

As good cause eviction laws grow in popularity across the country, it will become increasingly important to track and document instances of implicit and explicit state preemption.

Qualitative and quantitative data demonstrating the promise of good cause eviction laws in advancing racial justice can influence statewide policy change.

Coalitions are most effective when they represent different jurisdictions and diverse voices within a state.

Studying the impacts of good cause eviction has been difficult because so few jurisdictions have succeeded in enacting it. In those few cases, gathering evidence to understand the impacts of these policy changes on the ground is crucial.

The severity of the U.S. housing crisis demands urgent and multi-pronged action. Our advocacy must anticipate potential implied preemption of good cause laws as we fight for tenant protections that advance racial justice at the local and state levels.

This article can also be found through Local Solutions Support Center.

New York’s housing crisis continues to worsen, and Black renters, particularly Black women have suffered most. TMI’s research calls attention to the need for a good cause eviction protection law to help address racialized inequites.

A survey found that Black, white, Asian, and Latino respondents back policy changes to allow more housing. This publication was produced in partnership between the Thurgood Marshall Institute, The Pew Charitable Trusts, National CAPACD, and UnidosUS.

When people with prior criminal legal contact are systematically barred from housing, the racial discrimination embedded in the criminal legal system gets infused into the housing market.

People who endure appraisal bias suffer financial fallout not because of the actual value of their home, but because of the color of their skin. The origins of this discriminatory practice date back decades.

In this LDF series, Sec. Julián Castro explores the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing Rule, and reflects on redressing the extensive barriers to quality housing for many groups in Los Angeles County.

LDF and the National Fair Housing Alliance report investigates housing discrimination in the voucher program in Memphis, TN, and identifies recommendations to ensure all renters have safe and affordable housing.